Do ambient AI scribes understand healthcare workers and patients in South Africa? A sandbox experiment

-5.png)

The promise of artificial intelligence in healthcare has moved from futuristic concept to practical consideration. Around the world, AI scribes are being piloted to reduce administrative burden and improve record keeping. Yet in South Africa, where conversations between healthcare workers and patients are linguistically rich, contextually complex and often multilingual, the question is more nuanced. Can ambient AI scribes truly understand us? At our data science consultancy, we set out to explore this question through a small, rapid experiment. We wanted to provide an initial evidence base for healthcare leaders who are asking themselves whether to use an AI scribe, and if so, which one.

A best-case test

We designed the simplest possible study: a sandbox experiment to test whether current AI transcription tools can handle typical South African medical conversations. We focused on English and Afrikaans to give the technology the best chance of success. In reality, South Africa’s linguistic diversity and characteristic code-switching make transcription particularly challenging.

A linguistics study from the University of Cape Town found 356 instances of switching between English and Afrikaans across just a few hours of group interviews. People shift between languages mid-sentence for reasons of comfort, nuance, identity and tone. That linguistic flexibility is part of how people communicate authentically, but it is far removed from the “textbook” English and Afrikaans on which most global AI models are trained.

If AI scribes are to serve South African patients and clinicians, they must do more than process neat sentences spoken in laboratory conditions.

Simulating real consultations

Because recording real doctor–patient conversations would raise privacy and ethical challenges, we simulated typical primary care consultations. Working with medical doctors, we wrote semi-structured scripts for common conditions such as lower back pain, diabetes and insomnia. We recruited two doctors and two trained actors as “patients”, deliberately choosing people known to switch between English and Afrikaans during natural conversation.

Each doctor conducted three simulated consultations. We used the built-in microphone of a standard laptop: nothing more sophisticated than what might be found in a clinic. In total, the recordings contained 3,746 words.

We then transcribed these conversations using several tools that claim to understand both English and Afrikaans. These included OpenAI Whisper, Google Gemini, ElevenLabs Scribe and Heidi Health. Of these, only Heidi Health is designed specifically for clinical transcription. The others are general-purpose systems. After transcription, we cleaned the outputs, removing speaker tags, timestamps and filler words to ensure fair comparison.

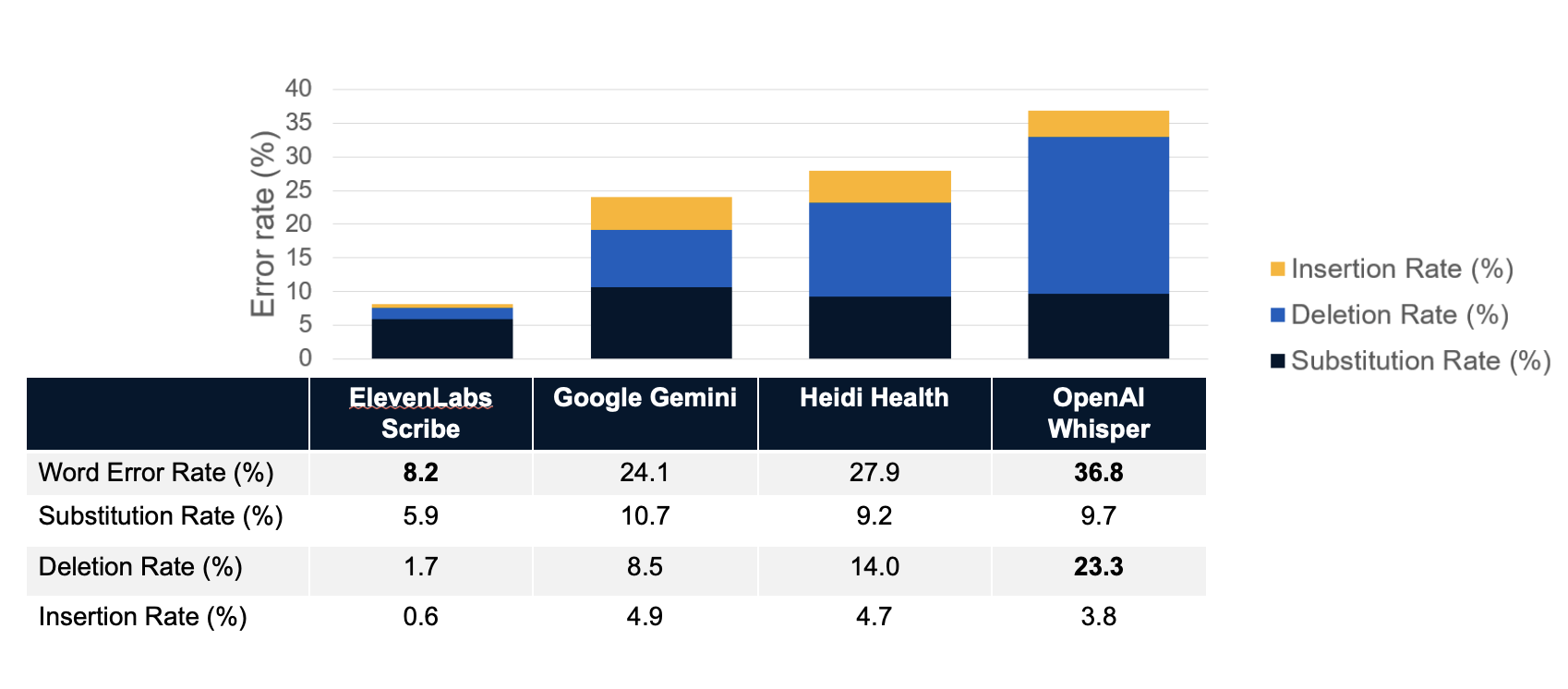

The key metric was the word error rate (WER), the percentage of words in the transcript that were wrong, missing or incorrectly inserted.

How well did they understand?

The results were striking. ElevenLabs Scribe performed best, with an average WER of about 8 percent. OpenAI Whisper performed worst, with around 37 percent. The difference was mainly in deletions: Whisper simply failed to capture roughly a quarter of the words spoken. Rather than misinterpreting, it often produced silence where meaning should have been.

For leadership teams considering AI scribes, this highlights an important lesson: not all systems are equal, and their accuracy varies dramatically depending on accent, recording quality and conversational style.

When imperfect transcripts still add value

Yet transcription accuracy is only the first step. In practice, few clinicians will read the full transcript of a consultation. What matters is the quality of the summary, the structured note that enters the health record. We therefore tested whether imperfect transcripts could still produce useful summaries.

The findings were encouraging. Even the weaker transcription systems were able to generate reasonably accurate summaries. In fact, the AI-generated summaries were often more complete than the notes produced by the doctors themselves. Doctors’ notes were typically short bullet points. The AI summaries, by contrast, captured more of the conversation’s context and were more structured, as they were prompted to generate SOAP (Subjective, Objective, Assessment, Plan) notes.

This suggests that a certain level of error in transcription does not necessarily prevent useful clinical documentation. For busy clinicians, this could mean better records with less manual effort.

What next for AI scribes in South Africa?

Our study was small, only six simulated consultations, and not designed to produce statistically definitive results. But it highlights several important considerations for healthcare leaders.

First, variation matters. Some systems are far better than others, and their strengths differ. The future likely lies in modular approaches, where organisations can mix and match components: one tool for transcription, another for summarisation, and a third for integration into electronic health records. No single system is likely to excel at everything.

Second, data security and privacy remain critical. Few healthcare organisations will be comfortable sending patient audio to global cloud providers without guaranteed data deletion. The alternative is to deploy open-weight or on-premise models, such as OpenAI’s open-weights Whisper models, in secure local environments, an option that requires more technical effort but offers control.

Third, integration is essential. An AI scribe that operates separately from the electronic health record will only add friction. The goal should be seamless workflows that improve rather than complicate the clinician’s experience.

Fourth, AI scribes could accelerate patient engagement. If automated summaries can be safely generated, they could be shared directly with patients, allowing them to revisit what was discussed, improving recall and adherence. This is standard in other digital domains but still rare in healthcare.

Finally, we should remember that transcription is not understanding. Even the best AI can only record what is spoken. It does not see non-verbal cues, body language or facial expressions. It does not sense hesitation, discomfort or the subtleties of human empathy. These are integral to clinical care and will remain uniquely human for the foreseeable future.

Building from here

Our small experiment is just a beginning. We plan to test additional tools, expand to more languages such as isiXhosa and isiZulu, and include a broader range of medical disciplines. We welcome collaboration from clinicians, technologists and health system leaders who are curious about how well AI scribes really perform in South African realities.

The opportunity is immense: to ease administrative burden, enhance the completeness of medical records and ultimately improve patient care. But the technology must first prove that it understands not just what is said, but how we say it.

Only then can we say that ambient AI scribes truly understand healthcare workers and patients in South Africa.

-6.png)

-13.avif)

-12.avif)